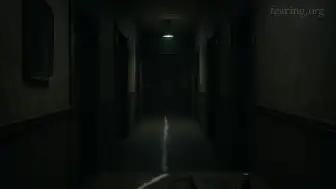

Throughout history, monsters have been more than just terrifying creatures—they’ve been mirrors held up to society’s deepest fears. From shambling zombies to seductive vampires, from cursed houses to malformed abominations, horror literature thrives not only on what frightens us—but on why we’re frightened. The genre's grotesque inhabitants are often symbols of real-world tensions, unspoken traumas, and shifting cultural anxieties.

"Every monster is a metaphor. Every scare, a reflection."

In this article, we’ll explore how horror literature uses monsters as metaphors to express social fears and psychological conflicts—from historical oppression and war to sexuality, class struggle, and the breakdown of identity.

The Monster as the “Other”: Fear of Outsiders

One of the most enduring themes in horror is the fear of the outsider—what is different, foreign, or unknown.

Dracula (Bram Stoker, 1897) embodies Victorian anxiety around immigration, sexuality, and disease. The Count is Eastern European, aristocratic, and sexually transgressive.

The Thing (John W. Campbell Jr.'s Who Goes There?) captures Cold War paranoia about infiltration and loss of individuality.

Aliens, in works like The Puppet Masters by Robert A. Heinlein or even Invasion of the Body Snatchers, often stand in for racial, cultural, or ideological threats.

These stories reflect xenophobia, nationalism, and fear of the unknown masked in monstrous forms.

Gender and Sexuality: Monstrous Women and Queer Horror

Horror has long grappled with gender roles and repressed desire:

The female monster (e.g., Carmilla, The Woman in Black) disrupts patriarchal norms by being seductive, independent, and dangerous.

Frankenstein’s creature (Mary Shelley, 1818) is often interpreted through a queer lens—his creation outside traditional reproduction and his emotional isolation parallel queer marginalization.

The Babadook (film, 2014) became an unexpected LGBTQ icon, interpreted by many as a symbol of internalized identity.

Feminist horror and queer horror subvert traditional roles and challenge normative structures.

Race and the Monstrous: Horror’s Reckoning with History

Race is a central, though historically under-explored, theme in horror fiction:

Beloved by Toni Morrison redefines the ghost story through the lens of post-slavery trauma.

The Ballad of Black Tom by Victor LaValle reimagines Lovecraft’s racist mythos through a Black protagonist’s eyes.

Get Out (film, Jordan Peele, 2017) became a cultural phenomenon for its blend of psychological horror and social commentary about racism and appropriation.

Monsters of color are often framed through racist stereotypes—but recent horror turns the lens inward to reveal who the real monsters are.

"The horror genre is finally asking: who’s monstrous—and who’s just marginalized?"

Economic Anxiety and Class Horror

Horror literature frequently emerges in times of economic instability. Class divisions manifest in stories where the rich are predators, and the poor are prey:

The Others (2001) and Parasite (2019) depict class disparity through the haunted house metaphor.

The Lottery by Shirley Jackson and The Hunger Games explore ritualized violence as social control.

The Purge franchise posits a dystopia where wealth protects and enables violence.

The home becomes a battleground between privilege and survival. These works reflect capitalism's darkest undercurrents.

War and Post-Traumatic Horror

Horror also reflects the psychic toll of war and violence:

The Haunting of Hill House (Shirley Jackson) features trauma and repression embodied in the house itself.

World War Z by Max Brooks is a zombie apocalypse novel that allegorizes global military policy and crisis management.

The Shining (Stephen King) parallels Jack Torrance’s descent into madness with generational abuse and alcoholism—often passed down like a curse.

"Haunted houses are often just haunted minds in disguise."

Science, Mutation, and Technophobia

Technological progress often inspires horror rather than comfort. Fears around mutation, surveillance, and loss of humanity arise when we exceed our boundaries:

Frankenstein remains the archetype of man playing god—and suffering for it.

The Fly, Annihilation, and Black Mirror stories confront fears of mutation, AI, and identity collapse.

Body horror—pioneered by writers like Clive Barker and filmmakers like David Cronenberg—explores the breakdown of the physical self as a metaphor for societal or psychological rupture.

In horror, progress often comes with a price.

Religious Horror: Blasphemy, Guilt, and Punishment

Religious trauma and fear of divine judgment shape many horror tales:

The Exorcist (William Peter Blatty) pits science and skepticism against ancient evil.

The Monk by Matthew Lewis (1796) showcases punishment for religious hypocrisy.

Carrie (Stephen King) reflects puritanical control and fear of female puberty.

These stories examine the boundaries between faith, fanaticism, and fear.

Environmental Horror: Nature’s Revenge

As climate anxiety increases, so too does horror based in environmental collapse:

The Ruins by Scott Smith features nature as predator

The Last of Us imagines a fungal pandemic consuming humanity

The Terror (Dan Simmons) mixes survival horror with nature’s indifference

These works frame nature not as a nurturing force, but as one reawakened—and enraged.

Contemporary Fears: Surveillance, Isolation, and Identity Collapse

Modern horror often reflects new psychological terrain:

Digital hauntings (Host, Unfriended) explore what happens when technology mediates all social interaction.

Isolation horror—especially during and after COVID—has become more internal, reflective, and existential.

Works like House of Leaves or The Silent Patient twist reality, language, and the self, challenging the reader’s perception.

Today’s monsters don’t always have fangs—they wear our faces.

Why We Need Monstrous Metaphors

They provide catharsis—processing fear through fiction

They give form to the formless: racism, capitalism, alienation

They let us confront the taboo safely

They evolve with culture, ensuring horror remains relevant

"To name the monster is to begin to understand the fear."

Final Thoughts

The monsters of horror literature aren’t just lurking in the shadows—they’re sitting at the dinner table, working in the office, scrolling on the phone. They’re our systems, our secrets, our selves. Horror doesn’t just want to scare us—it wants to show us something.

By decoding these monstrous metaphors, we begin to understand the world’s darkest truths—and maybe, through fiction, illuminate a path through them.

“We don’t read horror to escape reality. We read it to face what we fear is already true.”