The Tylenol murders are more than a true crime story — they mark a turning point in American trust, safety, and corporate accountability. In September 1982, seven Chicago-area residents died suddenly after taking extra-strength Tylenol capsules that had been laced with potassium cyanide. What followed was one of the largest criminal investigations in U.S. history — and a massive reform in how everyday products are packaged and protected.

“It wasn’t just the deaths that terrified people,” recalled journalist Scott Miller, author of The Tylenol Mafia. “It was the realization that something as ordinary as a painkiller could kill.”

Four decades later, the killer has never been found. But the impact of those seven deaths changed how the entire world consumes medicine.

The First Death

On the morning of September 29, 1982, 12-year-old Mary Kellerman of Elk Grove Village took a Tylenol for a mild cold. Within hours, she was dead.

Later that same day, Adam Janus, a 27-year-old postal worker, collapsed and died after taking Tylenol in Arlington Heights. As his family gathered to mourn, his brother and sister-in-law, grieving in his home, each took pills from the same bottle — and both died shortly after.

| Victim | Location | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mary Kellerman (12) | Elk Grove Village | Sept 29, 1982 | First victim |

| Adam Janus (27) | Arlington Heights | Sept 29, 1982 | Collapsed at home |

| Stanley & Theresa Janus | Arlington Heights | Sept 29, 1982 | Died from same bottle |

| Mary Reiner | Winfield | Sept 30, 1982 | Recent new mother |

| Paula Prince | Chicago | Oct 1, 1982 | Flight attendant, found dead in apartment |

By the end of that week, seven people were dead — all linked to Tylenol capsules purchased at different stores around Chicago.

The Investigation Begins

Police and the FBI launched a massive search to track the contamination’s source. Tylenol’s manufacturer, Johnson & Johnson, quickly pulled 31 million bottles — worth over $100 million — from store shelves nationwide.

Early theories included industrial sabotage, a disgruntled employee, or random tampering by a psychopath. But no factory contamination was ever found. Instead, investigators concluded that someone had purchased bottles, poisoned them, and returned them to store shelves.

“The killer wasn’t targeting individuals,” said FBI agent Roy Lane. “He was targeting trust.”

A City In Fear

Within days, Tylenol sales dropped 90%. Pharmacies posted warning signs. Police drove through neighborhoods using loudspeakers:

“Do not take Tylenol. Do not use it. Throw it away.”

Hospitals were flooded with patients who believed they’d been poisoned. Parents emptied medicine cabinets. Chicago, and then the nation, fell into a state of paranoia.

Johnson & Johnson faced the unthinkable: its flagship product had become a weapon. Yet the company’s swift, transparent recall — at a time when crisis management wasn’t even a concept — became a case study in corporate ethics.

“They put people before profit,” noted Fortune Magazine, naming the company’s response one of the most effective in history.

The Suspect Who Never Confessed

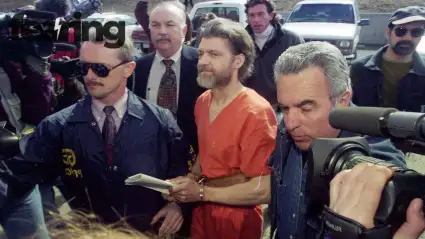

Within weeks, authorities received a ransom letter demanding $1 million to “stop the killings.” The note was traced to a man named James W. Lewis, who lived in New York and had a history of extortion.

Lewis was convicted of attempted extortion but denied any role in the murders. He served 13 years in prison and maintained his innocence until his death in 2023.

| Suspect | Accusation | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| James W. Lewis | Extortion letter linked to Tylenol murders | Convicted of extortion, not murder |

| Roger Arnold | Chicago resident, wrongfully accused | Cleared after evidence failed |

| Unknown individual(s) | Believed to have tampered bottles | Still unidentified |

Despite DNA testing, handwriting analysis, and thousands of leads, the killer has never been caught.

“This case haunts every investigator who’s touched it,” said Retired ATF Agent Linda Forrest. “We had the poison, the pattern, and the panic — but never the person.”

The Birth Of Tamper-Proof Packaging

Before 1982, over-the-counter drugs came in simple bottles, easy to open or alter. The Tylenol tragedy changed that forever.

Johnson & Johnson worked with the FDA to redesign packaging, introducing:

Triple-seal protection (foil seal, plastic wrap, and box glue).

Tamper-evident caps.

Public awareness campaigns about checking seals before use.

By 1983, the “Tylenol Bill” was signed into law, making product tampering a federal crime.

| Year | Change Implemented | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| 1982 | Nationwide recall of Tylenol | Saved public trust |

| 1983 | Federal “Tampering Law” | Criminalized tampering |

| 1984 | Industry-wide safety packaging | Became global standard |

“Every safety seal on your medicine owes its existence to those seven deaths,” said consumer safety advocate Dr. Lisa Brooks.

The Cultural Legacy

The Tylenol murders reshaped American psychology. Ordinary people learned to question what they bought, what they touched, what they trusted.

It also birthed a new genre of fear — the “invisible threat” narrative — later echoed in stories like Final Destination and Breaking Bad. True crime podcasts and documentaries continue to revisit the case, fascinated by how one anonymous act could shake an entire nation.

“It’s the most American crime imaginable,” wrote The New Yorker. “A story not about hatred or passion, but about the terror of ordinary life.”

Recent Developments

In 2022, the FBI confirmed new DNA tests were being run on surviving evidence, including fingerprints and residue from bottles. The agency also re-interviewed witnesses using advanced AI transcription tools to cross-reference statements.

Yet, after 40 years, no match has emerged. Some investigators suspect the culprit may have died — taking the truth to the grave.

“We don’t stop working just because time passes,” said FBI Special Agent Christopher Allen. “We owe those families an answer — even if it takes another lifetime.”

FAQ

Q1: How many people died in the Tylenol murders?

A1: Seven confirmed deaths occurred in the Chicago area in 1982.

Q2: Were the murders ever solved?

A2: No. The main suspect, James W. Lewis, was only convicted of extortion.

Q3: What was the poison used?

A3: Potassium cyanide, a highly lethal compound that causes respiratory failure.

Q4: Did the Tylenol company recover?

A4: Yes. Johnson & Johnson relaunched Tylenol with tamper-proof packaging and restored public trust.

Q5: Are tampering laws still in effect today?

A5: Yes, federal tampering laws remain a cornerstone of U.S. consumer safety.

Sources

FBI Case Archive – Tylenol Murders

The Guardian – Netflix Revisits the Tylenol Murders

Chicago Tribune – Inside the Tylenol Investigation

Smithsonian Magazine – How Tylenol Changed Packaging Forever

New York Times – The Poison That Shook America